There’s more to rhyme than meets the eye. If you want to write in rhyme, it’s essential that you learn meter. Let’s explore 4 types of meter below.

IAMBIC-An iamb is a metrical foot that starts on one soft beat and is followed by one hard beat.

TROCHAIC-A trochee is a metrical foot that starts on one hard beat and is followed by one soft beat.

ANAPESTIC-An anapest is a metrical foot that starts on two soft beats and is followed by one hard beat.

DACTYLIC-A dactyl is a metrical foot that starts on one hard beat and is followed by two soft beats.

It’s a common mistake to think that you need to count syllables in each line of your poem. It’s not necessarily syllables that matter though. It’s the STRESSED and unstressed syllables (in other words, the HARD and soft beats) that matter. It is possible to have varying numbers of syllables, but the same number of hard beats per line. It’s also possible (if meter is off) to have the same number of syllables, but an inconsistent pattern of hard beats.

It’s so important to keep a consistent pattern of hard beats. A line with two metrical feet (two hard beats) is called dimeter. Three metrical feet (three hard beats) is trimeter. Four metrical feet (four hard beats) is tetrameter. Five metrical feet (five hard beats) is pentameter. And so on! A poem as a whole can alternate hard beats per line, but the pattern should stay consistent for readability.

When your meter is inconsistent, your readers will be tripped up and your poem won’t read the way you’ve intended. Conversely, when you nail that meter, readability is greatly improved and your poem will sing! Is there some wiggle room for a headless iamb or a truncated foot, for instance, or an extra soft beat here or there? Yes. But the more consistent you keep your meter, the better!

Let’s look at some examples of each type of meter. Here is a stanza from one of my own picture book manuscripts:

The moon, you say? He thought he’d go.

So into space, he zipped!

He wished upon a shooting star

Then moonwalked, danced, and skipped.

Can you tell which type of meter I’m using here? If you guessed IAMBIC meter, you are correct! Each line starts on one soft beat and is followed by one hard beat. I’m also alternating iambic tetrameter (4 hard beats per line) with iambic trimeter (3 hard beats per line). Let’s look at the same stanza with the HARD beats in CAPS. It always helps me to get a visual for understanding.

the MOON, you SAY? he THOUGHT he’d GO!

so INto SPACE, he ZIPPED!

he WISHED upON a SHOOTing STAR

then MOONwalked, DANCED, and SKIPPED.

Do you see it now? It’s not so hard after all! The other important thing to keep in mind here is that we want those hard beats to fall where we would naturally place the stress on the word. Meter doesn’t work well when words are forced for the sake of the rhyme. Take the word “upon” from above, for example. We naturally say upON. We don’t naturally say UPon. For good meter, always aim to use natural language that isn’t forced. Now, let’s move on to another example.

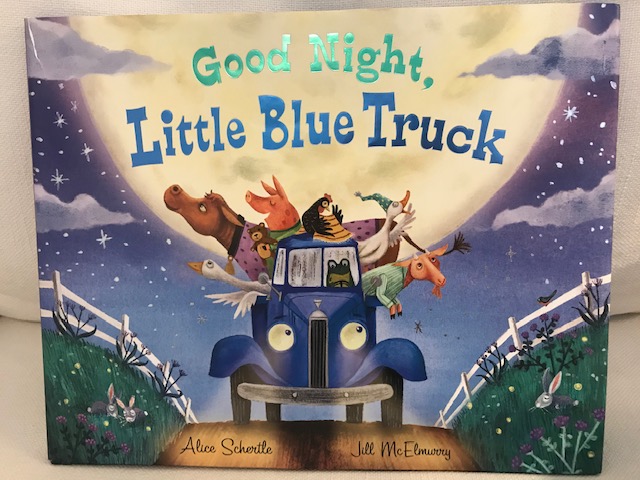

Good Night, Little Blue Truck by Alice Schertle

Do you hear it? Let’s look at the same lines with the HARD beats in CAPS.

THUNder CRASHing! LIGHTning FLASHing! TWO good FRIENDS were HOMEward DASHing.

While you will find variation and mixed meter in much of Alice Schertle’s writing, these lines are written in TROCHAIC meter.

Ready to keep going? Take a look at this line:

‘Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house…

And now, with the HARD beats in CAPS:

’twas the NIGHT before CHRISTmas, when ALL through the HOUSE…

Do you have it figured out? This is ANAPESTIC meter. Author Clement Clark Moore’s classic Christmas tale is a beautiful example of anapestic tetrameter.

We’ll look at an old nursery rhyme line for our last example:

Hickory dickory dock

HICKory DICKory DOCK

This line is an example of DACTYLIC meter. We see two dactyl feet (hard beat followed by two soft beats) and one truncated dactyl foot at the end of the line. A truncated metrical foot occurs when the hard beat is there, but the foot is missing one or more of the soft beats (in this case, the hard beat DOCK is there, but the soft beats are not). It may even appear as if the meter has changed, at times. And sometimes it’s true that you may have (for instance) a dactyl foot followed by a trochee followed by another dactyl foot. But usually, in meter that’s written well, there will be one dominant meter throughout, despite some possible variations.

There is so much to study about meter and rhyme schemes! I am only scratching the surface with this blog. I am a big believer in sticking to a consistent meter and pattern throughout a poem, but I recognize that many authors make mixed meter work as well.

Do you have a favorite type of meter? What are your biggest challenges when writing in rhyme? Leave me some comments if you found this blog to be helpful!

THIS is AmaZING!! (Did I emphasize the hard beats correctly?) Thank you for writing this! I will be referring to it for years to come!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Gennie, my wonderful CP!! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great article! I love the examples of classic texts. I’m glad if I ever decide to write in rhyme I’ll have you to help me fix it! 😊

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Lindsey, my other wonderful CP! 😄

LikeLike